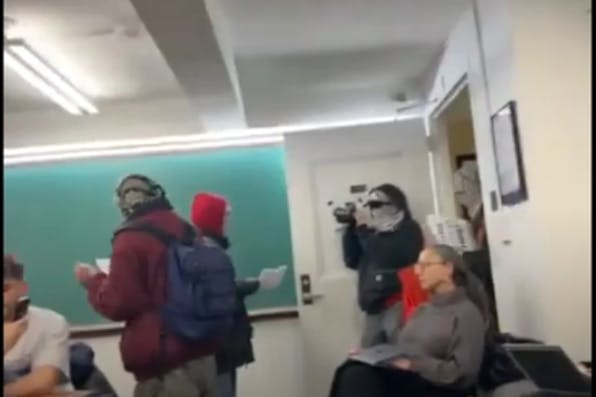

Since October 7, the decline of our universities has become clear to all but the most partisan observers. Outbreaks of anti-Semitism have become routine. Equally ominous is the rabid hostility toward the West and the founding principles—equality, liberty, and natural rights—of the United States. Such a moment forces us to consider some basic questions about the meaning of liberal education and the study of the Western tradition. It is especially urgent for Jewish students, the primary target of anti-Western hostility on campus, to understand the value of a liberal education.

The concept of liberal education emerges in ancient Greece. Perhaps the oldest definition is found at the beginning of Plato’s dialogue, the Laws: an “education that makes one desire and passionately love to become a perfect citizen who knows how to rule and be ruled with justice.” Liberal education is essential to justice and citizenship. In the Republic, Plato examines the nature of justice, and in doing so, raises doubts about whether it can fully be realized in political life. Yet justice is central to living a good life; in particular, without justice it is impossible to reconcile what we owe to our community and what we wish for ourselves.

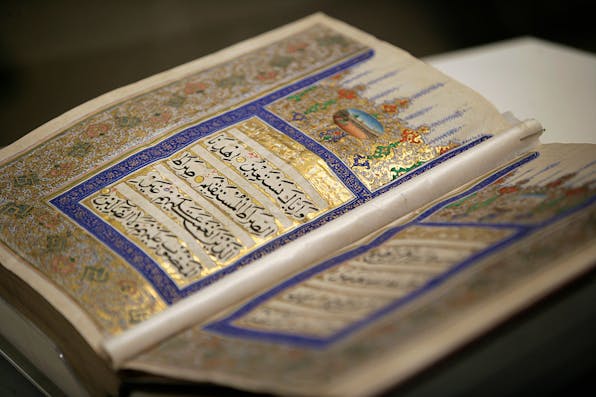

The focus on justice is central to the Western tradition for another important reason. The West is the product not only of the traditions that emerge in Athens, but also those that emerge in Jerusalem from the Hebrew Bible. The prophet Micah teaches that justice is the key to obeying God: “what does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.”

Athens and Jerusalem form together the foundations of Western Civilization. They both urge us to examine our lives and consider whether they are consistent with the best or highest way of life. They also teach that the best way of life involves a fundamental concern for understanding justice. But despite this considerable agreement, Athens and Jerusalem often disagree on the meaning of justice and on the question of the best way of life. Jerusalem takes its bearings from obedience to God and His commandments, while Athens has more confidence in the power of unassisted reason to discover a natural basis for justice.

Liberal education requires us to study and consider both traditions. The Western tradition provides an extraordinarily rich account of the interaction, not to say confrontation, between these traditions. The creativity and depth of these efforts is unparalleled. Judah Halevi, for example, presents the tension as a drama in his Kuzari, which makes the case for the superiority of Jerusalem over Athens. Yet he chooses to present his findings in the form of a dialog à la Plato. Around the same time, Maimonides writes a defense of Jerusalem for those students who have studied philosophy and found it difficult to reconcile fully with the Bible. His Guide of the Perplexed has since been recognized as one of the most profound defenses of Judaism. At the same time, it has been credited as preserving the deepest presentations of Plato’s teaching.

Clearly the tension between Jerusalem and Athens plays a central role in the meaning of Western Civilization. But this tension is not simply a relic of the past. The work of medieval authors such as Halevi and Maimonides had a profound impact on modern thought. To take one important example, the earliest attempt to define liberal democracy and explain it as the best regime is Benedict Spinoza’s analysis in his Theological-Political Treatise. Spinoza’s, whose family had fled the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal, was born in the displaced Sephardi community of Amsterdam. He studied carefully the medieval Jewish tradition before arguing that the Bible, if understood correctly, embraces freedom of thought and speech. He used this theological analysis to support a political argument on behalf of freedom and equality. Although some of his successors—Moses Mendelssohn, for instance—rejected his more radical claims, they nonetheless endorsed his program for liberal democracy.

While we recognize the power of Spinoza’s arguments for supporting our own liberal democracy, the story of the tension between Athens and Jerusalem hardly ends there. Some of Spinoza’s students followed his more radical line of thinking and pushed secularization to its ultimate limit of a wholly atheistic, socialist regime. Others were dissatisfied with the persistence of anti-Jewish sentiments. Leon Pinsker argues in Auto-Emancipation that Jews would never eliminate the prejudices against them because they were a nation without a state. Unless Jews became citizens in their own sovereign state, the promises of equality and freedom would elude them.

The point here, even in this short and incomplete outline, is that modern thought, including our doubts about the West, is very much the result of the ongoing tension between Jerusalem and Athens. The study of these tensions has become ever more pressing since October 7, and perhaps for Jewish students in particular. We cannot understand ourselves, let alone defend the Western tradition, unless we understand that tradition and appreciate its depth and meaning. Liberal education is the study of this tradition through the very texts that animate it. These texts, the great books, force us to consider fundamental alternatives to resolve questions such as “what is justice?” and “how should I live?” Some students—and even some professors—will of course be tempted by slogans and easy solutions. But for those who are willing to embark on a life-changing search that considers the most fundamental—and therefore best—alternatives for how to live, they cannot do better than to pursue a liberal education.