When I began teaching Yiddish literature at McGill University in 1969, I did not yet know that a group of young professors had just founded the Association for Jewish Studies. But the following year, I, along with my McGill colleague, the philosophy professor Harry Bracken, attended the second AJS conference at Brandeis University, where most of its founders were clustered. Harry had hired David Hartman, who came to Montreal as rabbi of a local synagogue, to teach a course on Maimonides, and Harry’s being a Gentile made it easier for us to persuade the university to introduce these two positions, and to get local Jewish-federation support for the required seed money—$10,000 per appointment for three years after which the university would pick up the position if students had shown an interest. On this basis, our program soon added appointments in Bible, Talmud, Jewish history, Hebrew language and literature, and education (to help train teachers for the Canadian Jewish day schools). AJS grew correspondingly: the Protestant orientation of higher education was broadening, and Jewish studies was part of that expansion.

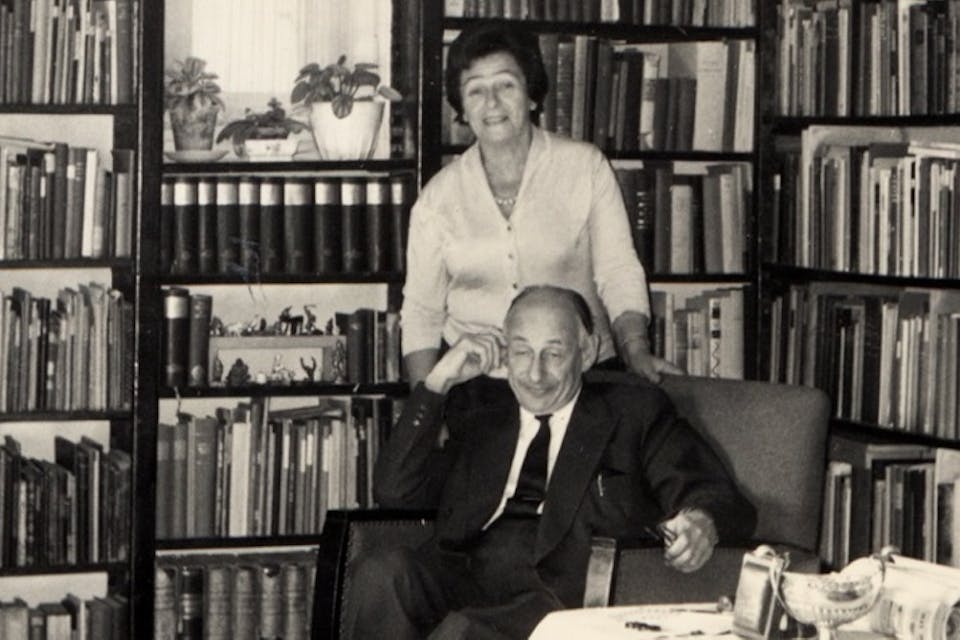

Although the AJS founders had not been able to persuade their teachers to join them in establishing this new organization, every conference honored one of those scholars: Salo Baron, Harry Wolfson, Alexander Altmann. . . . We respected the institutions that had trained us and aspired to improve the schools that hired us by adding the missing Jewish component to the study of our common civilization. When I joined the board, I was surprised by how eager my colleagues were to become part of the American Council of Learned Societies. They wanted to be held to the highest academic standards. We discussed requiring knowledge of Hebrew as a condition of membership but concluded it would be too hard to monitor, though you surely could not aspire to teach classics without knowledge of Latin or Greek.

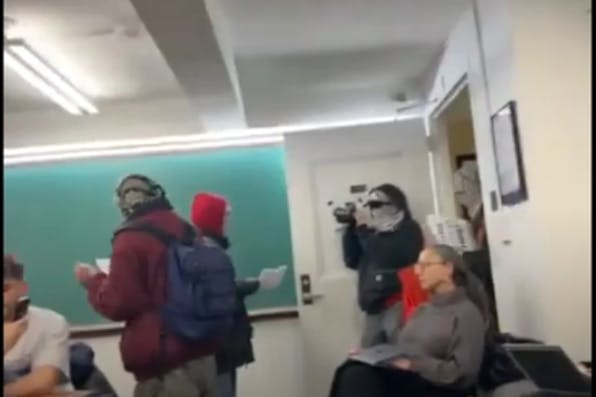

The introduction of Jewish studies coincided with the rise of what Lionel Trilling called the adversary culture, which was centered at the universities with the intention of transforming the country. The historian Paul Hollander associated the term with “a discernible and durable reservoir of discontent,” and a tendency to find the United States and its government at fault in every conflict in which it is engaged. Its adherents, including postmodernists, radical feminists, Afro-centrist blacks, and Marxists of various persuasions became the “tenured radicals” of the humanities and social sciences with rapidly growing influence over the next 60 years.

AJS at its founding was the antithesis of this adversary culture. With our disciplined presence we intended to shore up American higher education. We emphasized that the “Jewish” of AJS defined not the membership but the subject area. In advanced Yiddish seminars, where it was sometimes assumed that all were Jews, I said that the first-person plural pronoun referred to us students, not members of the tribe. This was meant to direct classroom discussion to literary analysis, moving personal and political conversations to the campus Hillel or office hours. The more actively others began blurring the boundaries between teaching and proselytizing, the more we insisted on the importance of “disinterested” inquiry in the academy. In 1985, the original founders persuaded me to take on the presidency knowing that I supported this distinction.

But no one could stem the tide. A Women’s Caucus formed, not for the academic study of women but to gain the power they thought they deserved in the organization and in their fields. American Friends of Peace Now, a group advocating that Israel yield territory to Palestinians formally committed to Israel’s conquest, organized meetings at the annual conferences promoting politics against the incumbent Israeli government. The adversarial culture not only penetrated the AJS but developed Jewish branches of every category of intersectional politics, emphatically including anti-Zionism. My own field of Yiddish was contaminated by association with leftism and marginality. The language my teacher Max Weinreich had defined as “the language of derekh ha-Shas”—of the talmudic way of life and learning—was used to show Jews as victims, socialists, aberrant, or “queer.”

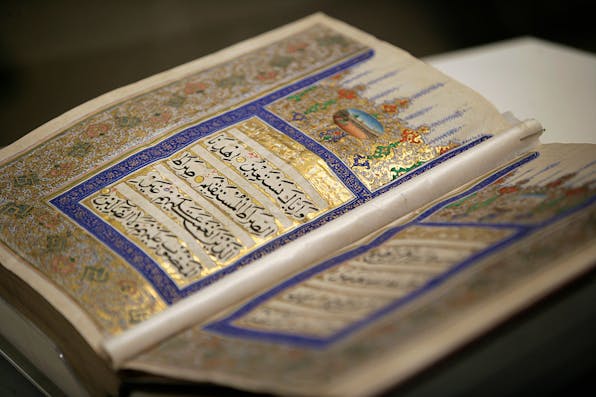

Jews represent the indomitably distinctive element in pluralistic societies. AJS set out to study all aspects of that distinctiveness in the context of investigative freedom. Our endeavor was never more important than during the recovery of Jewish sovereignty in the Jewish homeland which had been under foreign occupation for two millennia. The resilience of modern Jewry was reason enough to study its creative endurance.

All the sorrier that so many of its teachers flowed into the “discernible and durable reservoir of discontent” when they could have reinforced through confident transmission the divinely inspired teachings and experience of the Jewish people. The letdown to higher education was as great as the blow to Jewish honor. We must now see if a new generation of Jewish academics can reverse the damage.