August 11, 2025

Universities Need Teachers Who Want to Teach, and Students Willing to Learn

Make yourself a teacher, and get yourself a friend

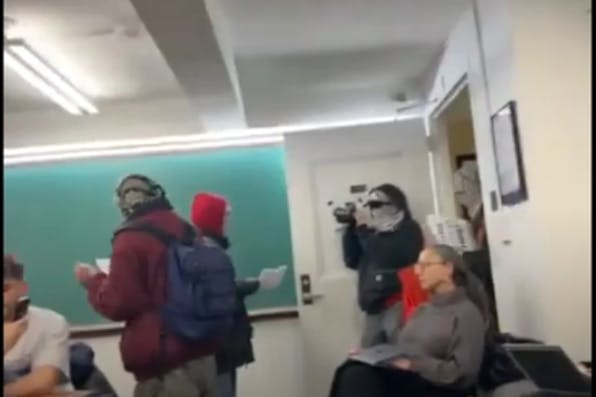

As a recent graduate of UCLA, I saw up close some of the worst excesses of the student anti-Israel movement: a massive encampment blocking access to the central part of campus, classmates chanting violent and vicious slogans, and an attempt to purge student government of “Zionists” (in practice, Jews). The last item led me to file a formal complaint with the university.

I’m not the first to point out that these problems, all too typical of American universities, are the result of a much deeper institutional crisis. I’d like to call attention to one aspect of this crisis, based on my own experience: the decline of mentorship, itself connected to the unwillingness of teachers to teach and students to learn.

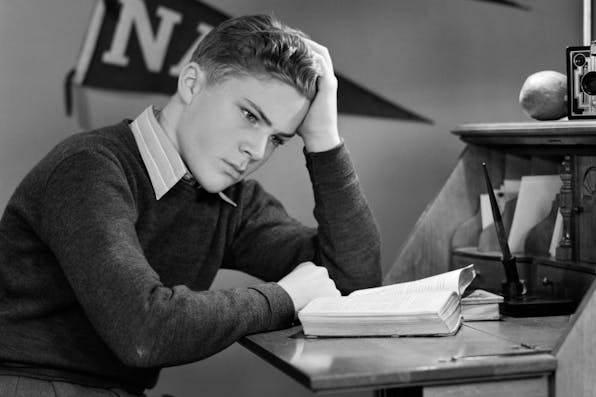

There’s a reason why mentorship is the subject of some of Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks’s most personal writings, the epitome of love in Plato’s Symposium, and the theme of one of my favorite films, Dead Poets Society. The wisdom in all three is the same: learning happens not just within the mind, but in the interaction between students and teachers.

Responses to August ’s Essay

August 2025

The Future of Higher Education and the Jews: A Symposium

By The Editors

August 2025

How Jewish Studies Became a Tool of Adversarial Culture

By Dr. Ruth Wisse

August 2025

The Future of Universities Must Be Built on Firm Values

By Daniel Diermeier

August 2025

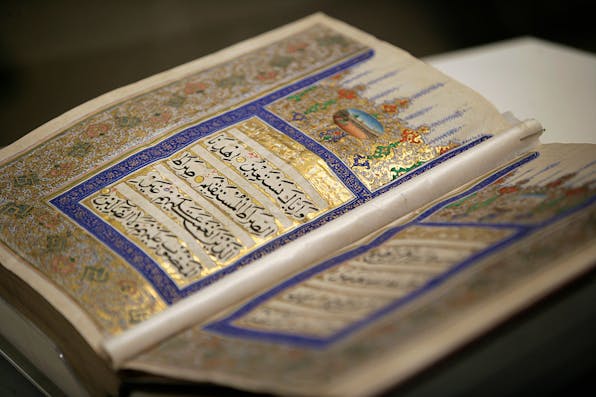

Western Civilization and the Jews: A Shared History

By Steven H. Frankel

August 2025

The Quest for Wisdom, Truth, and Virtue at the University of Dallas

By Jonathan J. Sanford

August 2025

Universities Need Teachers Who Want to Teach, and Students Willing to Learn

By Bella Brannon

August 2025

Saving American Universities Requires Cracking Down on Foreign Funding

By Danielle Pletka

August 2025

Jews Shouldn’t Give Up on Universities, and Neither Should America

By Eitan Webb

August 2025

The Moral Collapse on Campus Is a Result of the Hollowing Out of the Humanities

By Alexander S. Duff

August 2025

Return American Universities to Their Religion-Friendly Roots

By Liel Leibovitz

August 2025

To Make the Academic Desert Bloom, Look to Religion

By Ari Berman

August 2025

The Universities and the American Crisis

By Ben Sasse

August 2025

The Campus Intifada Is a Golden Opportunity for Those Who Study Israel Seriously

By Avi Shilon

August 2025

With No Easy Fixes for Middle East Studies, It’s Time for New Programs

By Robert Satloff

August 2025

The Perverse Microeconomics of the American University

By Michael Hochberg