January 11, 2021

What Zionism Did for Herzl

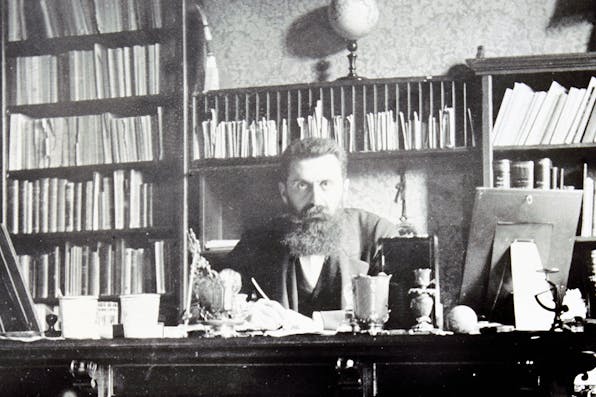

Though he was blessed with extraordinary charisma, Herzl was filled with inner turmoil. In Zionism, he found a calling that stabilized his fragile persona.

Rick Richman describes the story of Theodor Herzl as a “mystery.” Was it? To some degree we are all mysteries. No human can ever fully understand another—or, for that matter, him or herself. Herzl was a particularly complicated man whose neuroses were commensurate with his talents. But complexity is the opposite of mystery—it is an invitation to empirical investigation and a caution not to take our subject’s self-presentation, or his perception by others, at face value.

Many Zionists of Herzl’s era agreed with Richman’s comparison between Herzl and Moses. The artist Ephraim Lilien depicted him as Moses, the prince of Egypt who rejoined and redeemed his people, and as other biblical heroes such as Aron and Joshua. In his diary, Herzl likened himself to Moses, striving to lead a “procession of slaves.” However meaningful it was for Lilien and Herzl to make these comparisons, however, they should not form a typology of Jewish leadership because biblical figures are not necessarily historical ones. Even if we believe that Moses and Joshua existed, we cannot access their deeds, thoughts, and feelings beyond what an ancient sacred canon tells us. This is not the case with Herzl, a modern man who left behind a vast trove of literary, journalistic, and personal writings. Also, Herzl’s contemporaries recorded their interactions and impressions of him, throwing light on not only his leadership ability, acumen, and charisma but also his character flaws, blind spots, and failures.

Herzl’s turn to Zionism was the product of many factors. Richman emphasizes encounters with anti-Semitism in Paris and especially Vienna. But many European Jews of Herzl’s era were confronted by anti-Semitism, while few became Zionists. We must look as well to Herzl’s life-long aspirations for achievement and recognition. At the age of twenty-three, in the wake of his resignation from the Albia fencing club, the unhappy end of a love affair, and the rejection of his first plays, Herzl wrote that he was “overcome by the hopelessness of my existence. . . . Yet I need success. I thrive only on success.” Such feelings are common in adolescence, but depression, and the desperate search to relieve it via nonstop work and achievement, continued to afflict Herzl throughout his adult life.