January 25, 2021

Herzl Was the New Jew

From the soil of tsarist autocracy, no Jewish political leaders could grow. Herzl, by contrast, exuded the spirit of modern, fin-de-siècle Europe.

“Do you read Jewish newspapers, and did you notice the ‘original plan’ of someone, a Viennese journalist, who invented a new solution to the Jewish problem: establishing a Jewish state in Syria,” wrote Ḥayyim Hissin on July 23, 1896, to his friend Jacob Shertok, his pen dripping with irony. Hissin and Shertok were among the pioneers of the First Aliyah, who settled in Ottoman Palestine in the early 1880s; the latter was the father of Israel’s second prime minister, Moshe Sharrett. “Strange,” Hissin continued, “we say again and again the same thing, then suddenly somebody shouts it out very loudly and everyone think that they heard a completely new idea.”

Of course, as readers of Rick Richman’s essay will know, the “Viennese journalist” was Theodor Herzl, who—now as in Hissin’s day—is seen as the “the visionary of the Jewish state.” But Herzl’s idea of a Jewish state was not new. Leon Pinsker, a physician from Odessa, had written a more eloquent manifesto, Auto-emancipation—published in 1882, thirteen years before Herzl began writing The Jewish State—and pioneers like Hissin and Shertok had already established agricultural settlements in Palestine. Indeed, Zionism was a lucky movement: more than once it lost momentum and seemed on the verge of evaporating, and then something or someone appeared and brought it back to life. But Hissin did understand that Herzl was the person who could reanimate Zionism after a decade of oblivion.

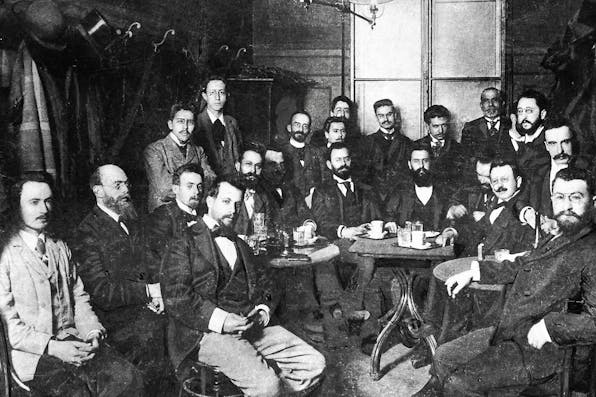

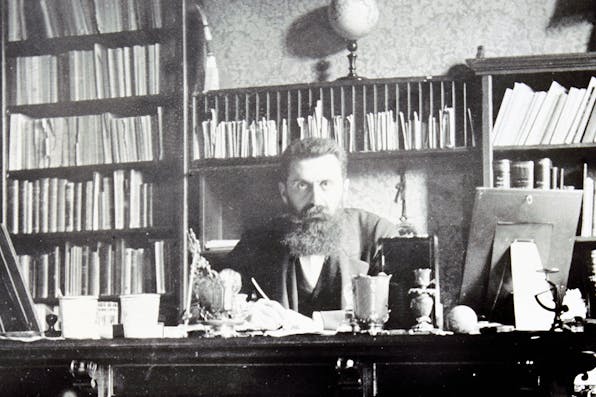

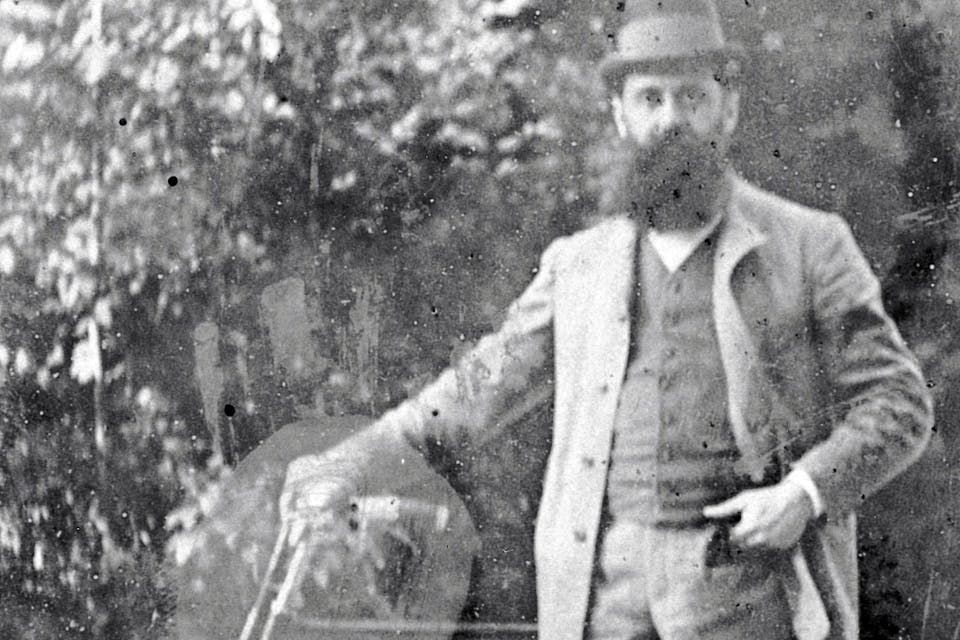

History chose an unpredictable hero. Who would have thought that Theodor Herzl, an assimilated Jew far from Jewish tradition, a journalist at home on Paris boulevards and in Vienna cafes, would suddenly devote ten years of his life to the resurrection of a people he hardly knew, and sacrifice his career, his family life, and even his personal finances for an idea that his social circle, and most of his contemporaries, thought to be an illusion? This is what Richman has rightly identified as the mystery of Theodor Herzl. Reading Herzl’s diaries, one has the feeling that he went through a transformation, a revelation, as if he heard a divine voice, making him a man of destiny. But the reasons for Herzl’s success need not remain entirely mysterious.