April 3, 2014

The Walter Benjamin Brigade

How an original but maddeningly opaque German Jewish intellectual became a thriving academic industry.

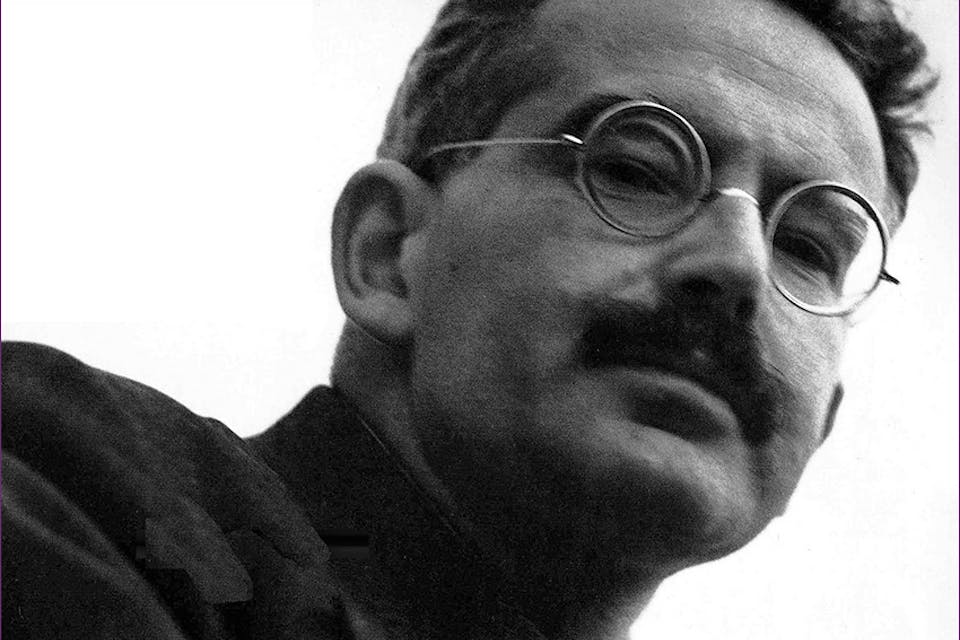

The German Jewish intellectual Walter Benjamin, born in Berlin in 1892, dead by his own hand on the French-Spanish border in 1940, remains a man of mystery. Anything but prominent in his lifetime, he has emerged in recent decades to unvarnished acclaim as the greatest thinker of the 20th century in fields ranging from philosophy to sociology, aesthetics, literary theory and criticism, and a half-dozen more. This in itself is mysterious. Among the ranks of mid-century Central European intellectuals, the reputation of Benjamin’s contemporaries and colleagues (with the possible exception of the Frankfurt School philosopher Theodor Adorno) continues to shrink; his continues to rise and rise. The number of books and articles devoted to him is staggering; a huge new biography, Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life, co-written by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings and published by Harvard, is only the latest addition to a seemingly unending stream.

How to explain the Benjamin vogue? Eiland and Jennings cite such cultural signposts as the radical student movement of the 1960s and the attendant revival of Marxist thought. But 60s radicals were hardly great readers, and Benjamin’s writings are, to say the least, maddeningly opaque and often altogether inaccessible. As for his Marxism, such as it was: if that is the main point of attraction, by rights the real culture hero should be his contemporary Herbert Marcuse (1898-1979)—once famed as the “father of the New Left” but, these days, decidedly not a name to conjure with.

More likely, Benjamin owes his fame to the rise of cultural studies and its various academic subdisciplines: post-modernism, post-structuralism, women’s and gender studies, and the rest of the lot. In these precincts, Benjamin’s gnomic style may well count as a plus, an outward sign of inward profundity that, simultaneously, invites the most fanciful flights of interpretive ingenuity. Likewise contributing powerfully to his allure is the sorry story of his life. Quite apart from his tragic end—he swallowed poison while fleeing from Nazi-occupied France—he was always the frustrated outsider par excellence, the very type of the marginal man. Indeed, had he lived, one can hardly picture him as a happy soldier among the academic janissaries of contemporary cultural studies.