July 20, 2017

Anglo-Jewish Attitudes

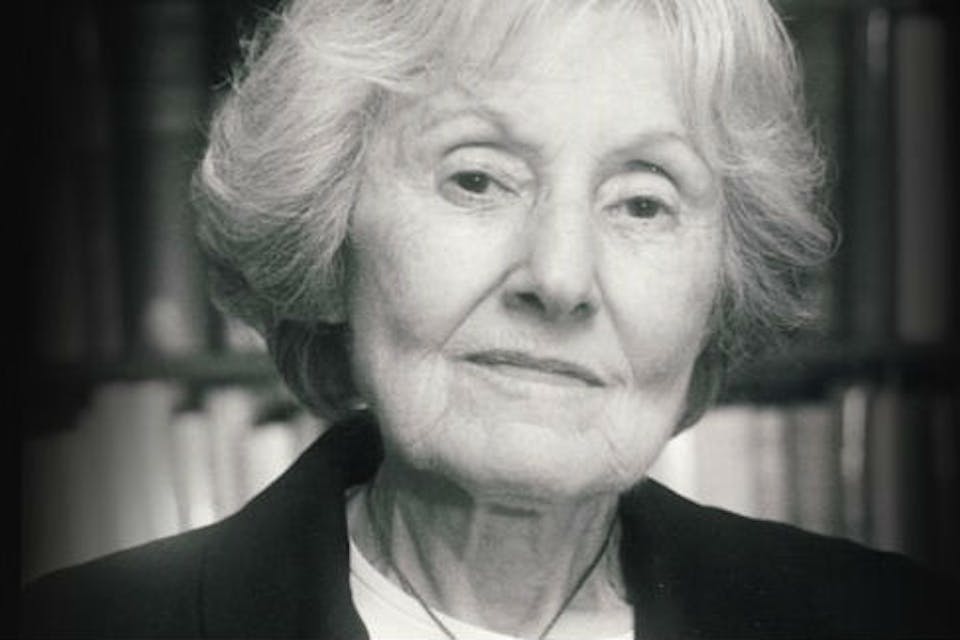

Gertrude Himmelfarb, historian of Victorian Britain and of the 18th-century Enlightenment, has lately devoted special attention to Jewish history and culture. What's the connection?

The cultural historian Gertrude Himmelfarb has arguably done more than anyone to shape our understanding of Victorian Britain. She has also written books on the 18th-century Enlightenment as well as numerous essays on the formation of 20th-century American culture and on contemporary politics and society. Her work, based on the careful and extensive accumulation of textual evidence, is a paragon of history-writing in the old style. Reviewing in Mosaic her latest collection, Past and Present, Peter Berkowitz has acutely pointed out the degree to which the body of her work stands as a powerful reproach to the writings of today’s postmodernist historians, whose accumulating misconstruals and distortions she has steadily and trenchantly criticized.

More recently, Gertrude Himmelfarb has also authored or edited several books on Jewish history and culture, especially in the English-speaking world. In what follows, I mean to direct myself to this area of her work and to her specific ideas about Jews and Judaism. But since those ideas cannot be properly appreciated without noting their place in her work as a whole, let’s begin by sketching the broader context.

In her book The Roads to Modernity (2004), Himmelfarb faulted historians of the 18th-century European Enlightenment for focusing primarily on the French experience and thereby slighting the markedly different course taken by the thinkers of the British or Anglo-Scottish Enlightenment and its American legatee. In her view, the main difference between the two Enlightenments concerned the status of reason. Whereas the French philosophes imbued reason with a quasi-religious sanctity and sought to reform, or remake, society on its basis, figures like John Locke, Lord Shaftesbury, Adam Smith, and David Hume saw reason not as an end in itself but as a tool for social reform and the safeguarding of liberty. In order to accomplish that purpose, it was necessary to temper reason with the social virtues of compassion, sympathy, and mutual responsibility.