August 19, 2014

How to Rejuvenate Modern Orthodoxy

Modern Orthodoxy as it developed in mid-century America was dynamic, vibrant, challenging. Thanks to Open Orthodoxy, it will be again.

In his essay in Mosaic, Jack Wertheimer, building on the terminology of the historian Jeffrey Gurock, divides today’s Modern Orthodox world into “resisters [of modernity] attracted by haredi Judaism and accommodators more willing to adapt Jewish law to 21st-century ethical sensibilities.” Given my professional position, I guess I would be placed in the accommodators’ camp. But it is not the goal of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School to produce rabbis who accommodate Judaism to the Western world. Rather, our aim is to harness the gifts of modernity in enabling us to learn and understand more Torah and to live lives that better connect us to God, the Jewish people, and the world: the goal of Modern Orthodoxy in general.

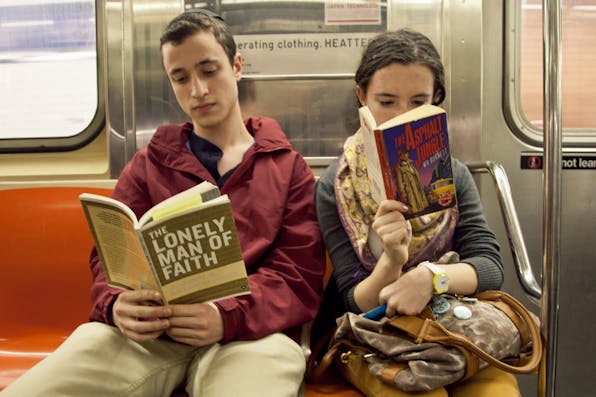

Modern Orthodoxy as it developed in 20th-century America was dynamic, vibrant, challenging, and filled with new insights into Judaism. This was made possible not by taking in the values of modernity wholesale but by maintaining a positive attitude toward those values and not opposing them merely because they were foreign. At its best, Modern Orthodoxy represented an embrace of the idea that the world around us could help Jews, not just hurt them. It is this Modern Orthodoxy, willing to listen to voices from without and within, that we need to revitalize.

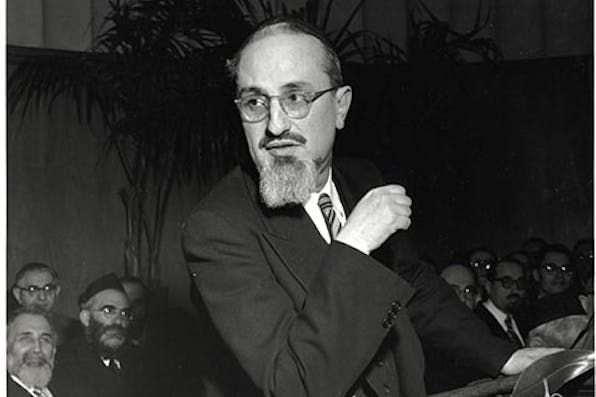

This is the very paradigm that was under siege twenty years ago when Rabbi Avi Weiss wrote his “Open Orthodox Manifesto.” Important and controversial Orthodox thinkers, including Rabbis Yitz Greenberg and David Hartman, were being shunned by the so-called Modern Orthodox establishment. Even Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, the founder and former spiritual leader of New York’s Lincoln Square Synagogue, was not allowed to speak at Yeshiva University. There was a sense of despair that the Modern Orthodoxy of the 1950s and 1960s—an era in which Rabbis Emanuel Rackman, Yitz Greenberg, and Eliezer Berkovits, and (in Israel) the philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz, were household names—had been lost. Even as Rabbi Saul Berman’s Edah initiative, noted by Wertheimer, succeeded in restoring a certain pride in the name Modern Orthodox, there was legitimate concern that the movement was coming to represent an ossified and unimaginative type of Judaism, always looking fearfully over its right shoulder. Hence “Open Orthodoxy.”