March 9, 2015

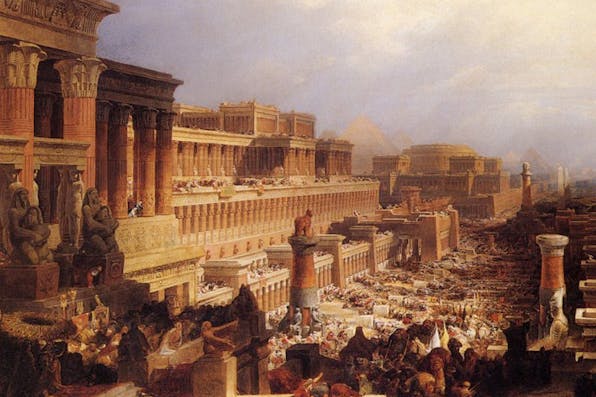

How to Judge Evidence for the Exodus

An event like the exodus can’t be "proved" in the manner of a scientific experiment. The way to judge is through the adding-up of suggestive details and reliable witnesses.

Since I’m in general agreement with Joshua Berman’s analysis in “Was There an Exodus?,” I’d like to focus here on amplifying a few of his central points.

Early on in his essay, Berman summarizes the core case against the historicity of the exodus: namely, “a sustained lack of evidence.” The written record of ancient Egypt is silent both on the presence of Hebrew or Israelite slaves and on their subsequent departure. In response, Berman provides several reasonable explanations for such a lack of direct evidence, whether written or archaeological, and aptly quotes the cautionary maxim that absence of evidence does not necessarily constitute evidence of absence. Then he proceeds to offer evidence of a circumstantial but highly suggestive kind. A whole series of details in the biblical story, he writes, “do strikingly appear to reflect the realities of late-second-millennium Egypt—the period [under Ramesses II] when the exodus would most likely have taken place.” Moreover, and very significantly, these details are of the sort “that a scribe living centuries later and inventing the story afresh would have been unlikely to know.”

All this is well put, and it can be buttressed. On the issue of the weight that can be assigned to absence of evidence, consider this: if a significant number of slaves escaped during the reign of a self-possessed pharaoh like Ramesses II, one would hardly expect him to advertise the fact. To the contrary, such information would be well hidden, especially by a regent who glorified himself in a manner exceeding other pharaohs before and after him.