August 16, 2021

Did Jabotinsky Really Mean it or Was He Pandering?

Although the Zionist leader tried to avoid statements that didn't reflect his true beliefs, he wasn't above doing so altogether. His late-in-life friendliness to religion might be one such case.

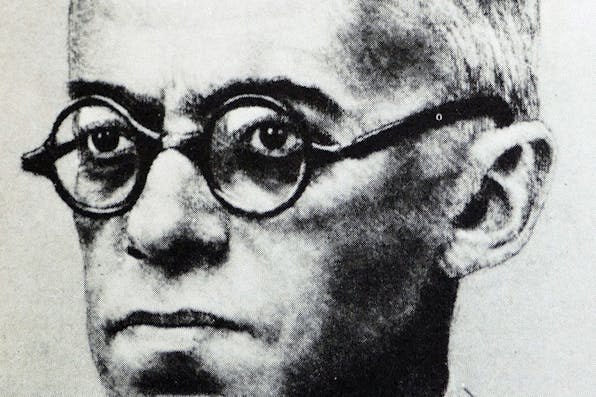

As the “prominent exception” cited by Avi Shilon to the view that Jabotinsky was a “staunch secularist” all his life, I find myself in agreement with nearly everything in his essay. My one caveat is with his assertion that “Hillel Halkin has shown in his biography that Jabotinsky was never quite so assimilated as he claimed to be.” Jabotinsky, whose mother spoke mainly Yiddish, punctiliously lit Sabbath candles every week, and saw to it that her son was taught Hebrew as a boy in Odessa, never claimed to have been any such thing. His supposedly assimilated background was the invention of those who mistakenly considered his European education, his journalistic and literary career in Russian, and his being comfortably at home in the world of Western culture to be signs of an un-Jewish upbringing.

Although Shilon’s essay touches on various aspects of Jabotinsky’s political career and thought, its main concern is Jabotinsky’s change of attitude toward religion in his later years. Here, too, there is nothing I would take issue with. Such a change indeed took place, and it took place along the lines Shilon describes. He is correct, too, in observing that it was Jabotinsky and his Revisionist Party that first laid the basis for the eventual alliance of right-wing nationalism, religious Orthodoxy, and Israel’s Mizraḥi population that brought Menachem Begin to power in 1977 and has made the Likud the dominant Israeli political party ever since. Although Jabotinsky, unlike Begin, never deliberately courted Mizraḥi Jews (who formed a small part of Palestinian Jewry in his lifetime), let alone appealed to whatever anti-Ashkenazi resentments they may have had, his militancy toward the British and Arabs, his pro-free enterprise views, and his sympathy for Jewish religious tradition spoke to them. During the last years of the British Mandate, they were far more active in the Irgun, the anti-British underground force affiliated with the Revisionists, than they were in the mainstream, left-leaning Haganah.

Was Jabotinsky entirely sincere in his intellectual embrace of Jewish tradition toward the end of his life? Avi Shilon does not doubt that he was. I sometimes wonder. Not that I would accuse him of hypocrisy. Few politicians have ever been as honest about their opinions and motives. His reevaluation of the social role of religion, and especially of Judaism, was genuine. One grows more conscious as one grows older of many things: of human frailty; of the insufficiency of purely rational answers to the deeper questions posed by existence; of the hunger for transcendental meaning that such answers can never provide; of the ineradicable reality of evil and the need to combat it by invoking a law higher than utilitarian or liberal principles. These were all things that Jabotinsky felt keenly.