June 15, 2023

Anti-Modern Anti-Semitism

The cultural chaos of the current era seems to map perfectly onto the anxieties of the 19th century. The same goes for today's flavor of anti-Semitism.

Back in 2017, when Donald Trump was newly inaugurated to the American presidency, and what was then known as the alt-right was riding its brief Internet-fueled period of chaotic cultural ascendancy, some of the right’s most esoteric and extreme thinkers began to tip their intellectual hand. Most prominent among them—at least in the United States—was Steve Bannon, at one time Trump’s ideological right-hand-man, who in a February 2017 speech to the Vatican made headlines by alluding to one of the 20th century’s most controversial thinkers, the Italian mystic, occultist, and self-proclaimed superfascist Julius Evola. At surface-level, it was an offhand reference—Bannon was describing Alexander Dugin, a similarly occult-minded Russian philosopher whose relationship with Vladimir Putin was sometimes compared to Bannon’s own with Trump. But to those attuned to the history of the mystic 19th-century movement known as Traditionalism, it was a revelatory dog-whistle, perhaps even a key to Bannon’s whole ideology. Like many of the figures central to the movements known as “neo-reactionary,” “alt-right,” and more recently, the “New Right,” including the British philosopher Nick Land, and the pseudonymous, improbably ubiquitous Twitter author known as Bronze Age Pervert, Bannon has a well-documented interest in Western esotericism, and in particular the sort of Traditionalism espoused by Evola.

This Traditionalism was deeply rooted in the tensions of the 19th century. Briefly summarized, it involves a belief in the transmission of a secret spiritual wisdom to chosen initiates—a wisdom underpinning the world’s more seemingly accessible organized religions. As liberal democracy, political equality, and industrial urbanization transformed the European landscape, those most ill-at-ease in the changing social order often sought refuge in an atavistic conception of the imagined past, in visions of biological rootedness inextricable from Volk mythology and “national epic,” in visions of (what they saw to be) pre-Christian or pagan mythologies that celebrated natural and spiritual hierarchies. Such visions centered around the person of a heroic (and usual Aryan) warrior whose strength and inborn position in the dominance hierarchy would be a vital counterweight to the faceless throngs of the modern urban crowd, in which everybody and every community is identical, exchangeable, and indistinguishable.

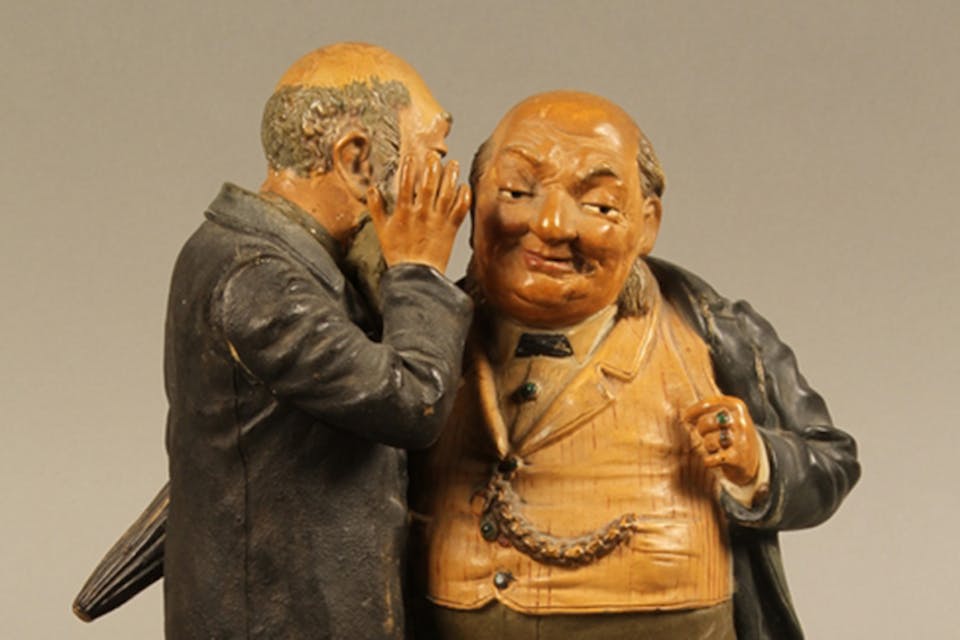

And, as Tamara Berens’s recent Mosaic essay, “From Coy to Goy,” makes clear, this ideology had both an implicit and explicit villain: the Jew. The Jew was coded as the “rootless cosmopolitan,” the disloyal outsider who controlled not things-in-themselves—not land, not rivers, not farms, not even, as John Ganz notes in his recent excellent essay on reactionary modernism, machinery—but instead only something magical and disembodied: capital itself. The Jew was in this schema the ultimate modern man, whose trade was not in the earth, or indeed in anything material, but rather in the realm of speculation: in money, in ideals. And so the Jew became the scapegoat for a century’s worth of frustration with Enlightenment modernity, with democracy, and with what was seen as a society uprooted.

Responses to June ’s Essay

June 2023

Anti-Modern Anti-Semitism

By Tara Isabella Burton

June 2023

Unchurched Christians and Anti-Semitic Ones

By Timothy P. Carney

June 2023

What American Conservatives Can Do about Right-Wing Anti-Semitism

By Tamara Berens

June 2023

Watch Douglas Murray, Samuel Goldman, and Tamara Berens on Anti-Semitism and the Battle for the American Right

By The Editors