October 10, 2019

How Jews Solved the “Design Problem” of Gesturing to the Prohibited Name of God Without Actually Writing It

The story of the three yods and other religious and aesthetic innovations.

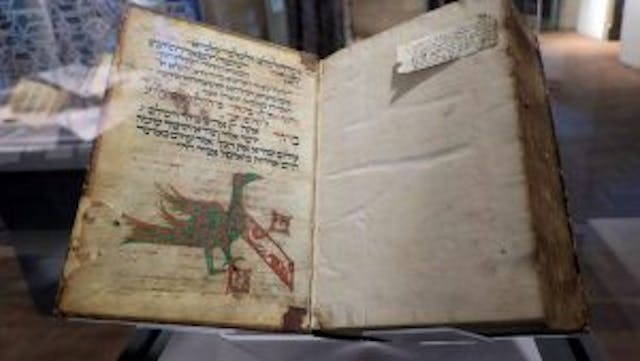

With its breast and one of its feet, the green-and-red bird at the bottom of a 14th-century manuscript page forms the leftmost leg of an aleph. The oversize aleph itself, “decorated,” or weighed down, with three other monstrous forms, appears beneath a section of the morning service from a prayer book likely originating in the Franco-German Rhineland, a region then controlled by the Holy Roman Empire. In the 15th century, in an instance of forced interfaith recycling, the whole manuscript page, complete with its bizarrely fantastic aleph, was reused to bind an edition of a Christian theological work.

Another, less conspicuous verbal symbol also appears several times on this same prayer-book page, which is itself part of the exhibition The Colmar Treasure: A Medieval Jewish Legacy at the Metropolitan Museum of Art Cloisters (through January 12, 2020). In its own way, that symbol is no less striking than the aleph, at least to the unpracticed eye. It is this: instead of writing out the Tetragrammaton—the four-letter, never-to-be pronounced Hebrew name of God, the scribe has substituted two yods, followed by what looks like a swirly kind of lamed that has lost one of its legs.