August 2023

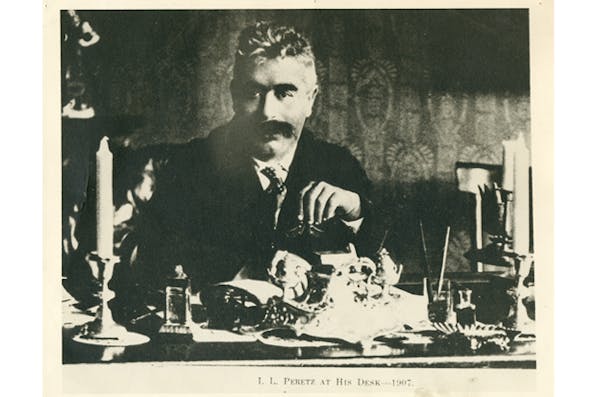

I.L. Peretz and the Golden Chain

The great Yiddish writer envisioned an unbroken transmission of Jewishness through the generations, from biblical prophets to talmudic sages to literary giants like Heine—and himself.

In September of 2015 I attended an international conference in Poland devoted to the centenary of the death Yitzḥak Leybush Peretz (1852–1915), the most influential Jewish writer of his time. The four sponsoring organizations, each with a strong stake in ensuring the country’s democratic future, were the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, the Polish Association for Yiddish Studies, the Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland, and the International Research Center on East European Jewry of the Catholic University in Lublin. Poland’s treatment of its sizable Jewish population had always been a gauge of its liberality, and Peretz represented that ideal: he had written some of his first poems in Polish and had briefly practiced law in his native region at a time when the emergence of a Polish-Jewish symbiosis seemed as possible as the fused identity of the American Jew.

Part of the conference was held in Zamość, Peretz’s birthplace, in the refurbished main synagogue on what is now Peretz Street, ulica Pereca, just off the city square—the rynek, or marketplace, that figures prominently in Peretz’s memoirs and literary works. The mayor extended us his personal welcome, paying our return bus travel from Warsaw. Several of the young Polish scholar-participants introduced fresh material on the author from their research in Polish sources and the Polish press. All this was heartening, yet most conspicuous was the absence of a single local Jew in a city where Jews had constituted about half the population between 1800 and 1939. It was in that synagogue, haunted by that knowledge, that I presented my paper on “The pursuit of justice in Peretz’s work.”

While no great writer can be represented by a single theme or subject, literature was for Peretz the extension of Torah for a modern Jewish people. Steeped in talmudic learning, he was fifteen years old when he entered “their House of Study,” as he referred to such marvels as the Napoleonic Code and European literature—the discovery of which forced him to straddle contrasting systems of theory and practice. What was the relation between sin and crime, between legal codes and their implementation? Did psychology’s new insights into human motivation affect the calibration of innocence and guilt? How could a minority like Jews or Poles under Russian rule attain political rights and what did they owe to one another in their parallel struggles? How did justice for women figure into human rights? Peretz assumed responsibility for fellow Jews who were quitting the yeshivas while keeping their prophetic-rabbinic tradition alive. If he could not represent them politically, he tried to be their voice and their guide through the story, poem, drama, and essay.