August 2024

How Western Artists Used and Abused the Hebrew Bible

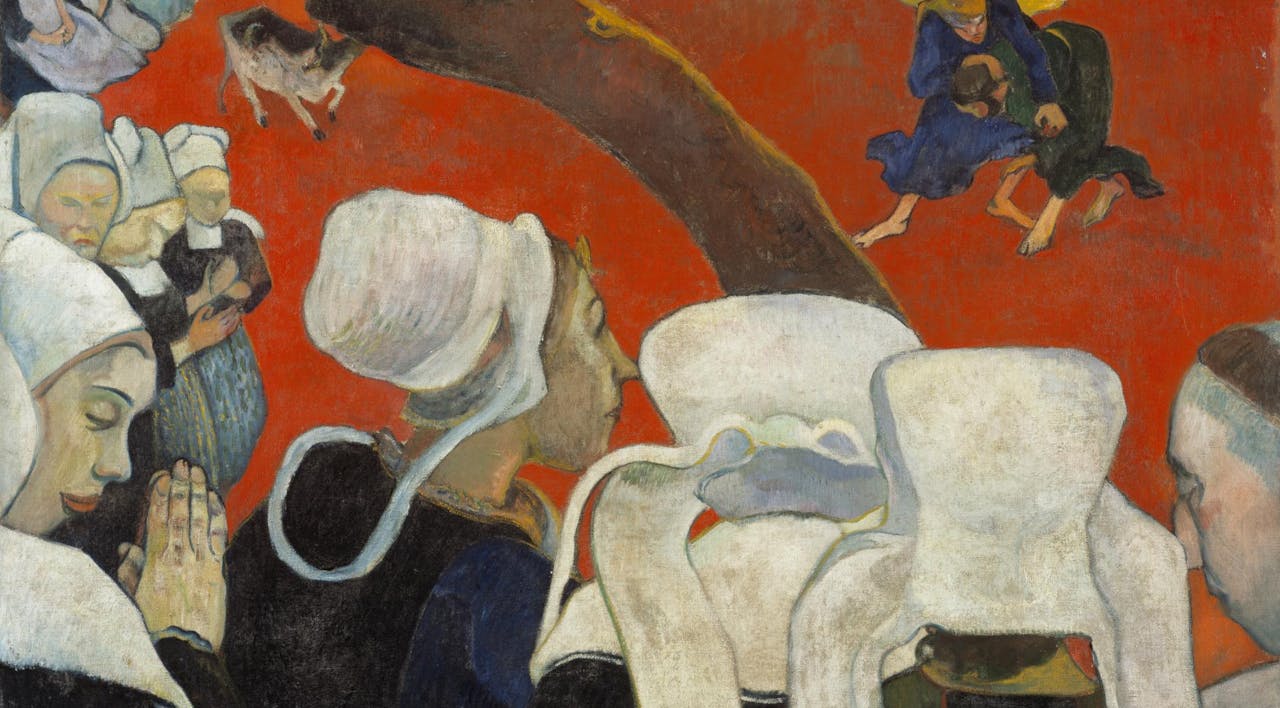

For centuries, visual artists, nearly all Christian, turned to the Hebrew Bible for inspiration even more often than the New Testament. What did they find there, and did they treat it well?

A number of years ago, in the course of teaching a survey of Western art from late antiquity to the modern era, I was struck by how many of the works we discussed in class were based on episodes from the Hebrew Bible. Considering this, I initially ascribed the frequency to my own predilection for these subjects. I must have been increasing the Hebrew-biblical content so as to focus on a narrative and religious tradition in which I was raised, I thought. I also happen to teach at a school, Yeshiva University, whose undergraduate students generally come from traditional Jewish homes and whose mission is guided by Jewish values. Maybe I was tipping the scale toward such material to satisfy not only my own taste but the value system of my audience and institutional setting as well.

But the more I thought about it, the more this didn’t seem to explain the phenomenon. In surveys of Western art and art-historical textbooks—in which the greatest or most important art works and expressions of artistic patronage and culture are featured—there is really no avoiding subjects that come from the Hebrew Bible. They are an integral and constant part of the art-historical tradition and are linked to some of its greatest masterpieces, most significant stylistic developments, and richest forms of artistic expression. One would be hard pressed to tell the story of the development of art from late antiquity to the modern period without regularly using examples of art works based on episodes or figures from the constituent parts of the Hebrew Bible—from the Torah (The Five Books of Moses), Nevi’im (Prophets), and K’tuvim (Writings). Indeed, one could do so exclusively using such examples, for key stylistic and thematic innovations often occurred in the rendering of Hebrew-biblical stories, and some of the most recognized works of art depict Hebrew-biblical figures, Michelangelo’s sculpture of David and Rembrandt’s painting Moses with the Ten Commandments being only two of the most famous.

And this realization led to another—one that made me less comfortable. While the subject matter of so much important art was taken from the Hebrew Bible, the spirit in which it was produced was less related, skewed from its source. For every David, echoing the biblical ideals of individual sacrifice, providential guidance, and good triumphing over evil that are rooted in the story of David’s triumph over Goliath, there are also numerous works that upend or overturn longstanding Jewish interpretive tradition. And while Rembrandt’s depiction of Moses presenting the Ten Commandments may reflect, as has been suggested in these pages, a distinctly Jewish perspective on the moment when Moses descends from Mount Sinai with the second set of tablets of the law, there are many more paintings and sculptures from the Western tradition that play loosely with Jewish interpretation, if they do not downright subvert it. Many of the Catholic Church’s most stingingly anti-Jewish theological pronouncements were expressed through visual programs and were absorbed into the vernacular religious tradition not through texts but through church altarpieces, domestic icons, and personal prayer books.